The Self-Sorting Silo

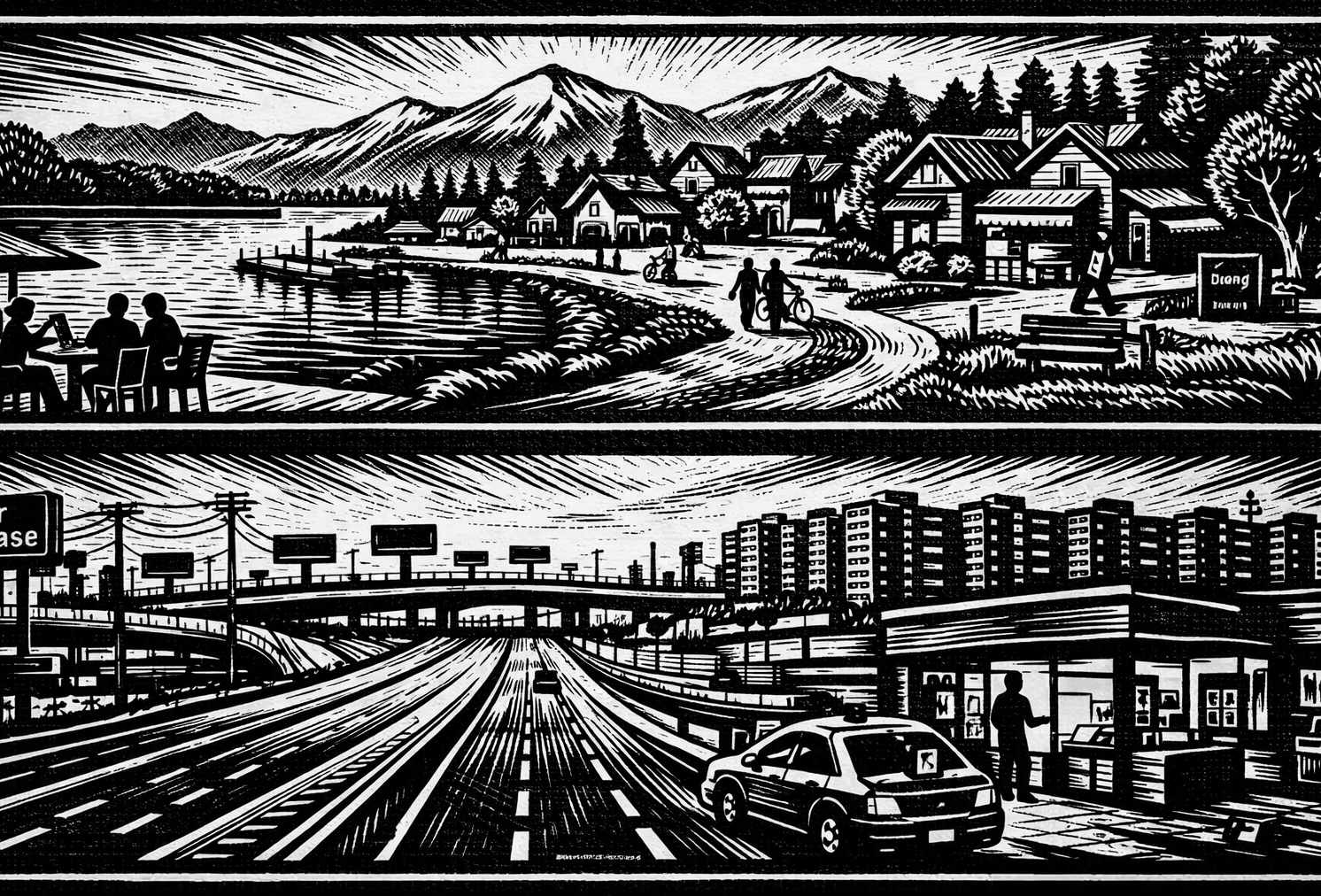

People talk about some places like they were always meant to exist. Lakes that hold light until late afternoon. Beaches where the wind has room to do what wind is supposed to do. Mountains that interrupt the world and remind you it can still be bigger than your schedule. Forests that are not an accent, but a presence.

When you arrive, you understand the pull immediately. It is not just beauty. It is what the place does to your body. You walk slower. You sleep deeper. Your mind stops running ahead of you for a while.

That is the top level of the silo.

It is not a utopia. It has rules, costs, and quiet pressures. But the baseline is humane. The days feel usable. Even the hard work feels like it belongs to a life, not like it is being extracted from one.

The streets are narrower. The sidewalks feel maintained because they are used. The parks feel intentional. The built environment carries a message. Homes look like they will still be homes in thirty years. Roofs do not look temporary. Yards do not look like apologies. Even when housing is expensive, it has a kind of permanence. It signals, in a hundred small ways, that the future is assumed.

Then you drive long enough, and the light changes.

The bottom level of the silo begins with width.

Eight lanes, then more. Long ramps built for volume. Concrete that radiates heat. A sky that feels closer because the landscape is flat and the horizon is made of signs.

In some places it still looks like momentum. Cranes. Fresh paint. New lanes. New units. It feels like arrival. But the shape is the clue. Build fast, build wide, build identical, and you are not building a city. You are building a holding pattern.

The apartments appear in grids. Windows like pixels. Minimal balconies. Parking lots that stretch wider than the buildings themselves. From a distance it reads like growth.

Up close, it reads like churn. A brand-new building fills fast. The one across the street lags, then catches up, then lags again. Some units sit empty while other units turn over constantly. The place stays fed, but it does not settle.

Not with collapse. With drift.

Sidewalks buckle and stay buckled. Streetlights blink out for weeks. Repairs get chosen for speed, not durability. Corners where people used to gather become storage, or nothing at all.

Then the strangest change arrives.

Not visible at first.

Audible.

On certain blocks, in certain office parks, the air has a new kind of quiet. The buildings are still there. The tinted windows still reflect the sky. The lobby still smells faintly of carpet and lemon cleaner. But the noise that used to leak out is gone.

No lunchtime surge. No clusters of twenty-somethings spilling into the sun, laughing too loudly, holding badges, living on iced coffee and hope. No entry-level churn. No new hires learning the names of things. No supervisors repeating themselves. No meetings that run long because somebody has to ask the basic question.

Just a few cars, parked far apart.

This quiet does not show up first in boom places. It shows up last. First the buildings fill. Then they overfill. Then the work changes shape. Then, one day, you notice the parking lot is half as full as it used to be and nobody can name the week it happened.

Inside, the light is on, but it is the light of a place being maintained, not the light of a place being filled. Screens glow behind glass. A receptionist is gone. The phones do not ring the same way. There is less paper. There are fewer voices. The work still happens, but it happens in a flatter rhythm, like a heartbeat medicated into calm.

You feel it in the people who used to be the first rung.

The runners, the coordinators, the assistants, the juniors. The new kids with decent clothes and nervous smiles. The ones who would have been busy, even if the work was boring, because busy was the way you earned your next step.

Now you see them elsewhere.

Standing behind counters where a screen tells them what to say. Tapping, reading, nodding, smiling at the right time. Orders arriving with little pings, and the pings setting the pace of the hour. The screen does not yell, but it does not forget. It does not get tired. It does not forgive in the human way. It just keeps moving, and the person moves with it.

They are doing what people do when the ladder in front of them becomes a wall.

And still, people arrive.

Because the bottom level is where life becomes possible for more people.

The rent fits. The commute is survivable. Someone you trust is ten minutes away. You can borrow a truck. You can get a kid picked up. You can show up late once and not lose everything. You can fail quietly and recover.

People arrive for reasons that make sense one at a time. A job followed. A family nearby. A first identity formed in a specific zip code. It is acclimation. The place wraps itself around you slowly, until leaving feels like stepping out of your own life and trying to build a new one from scratch.

That is the real cost. Not the moving truck. The restart.

It replaces the friction of ambition with the friction of basic survival. Logistics that eat your time. Schedules that leave you too depleted to plan. When a person is exhausted long enough, the future shrinks into something you visit in your head, briefly, and then put away.

Then you notice the quiet shame that grows in that kind of fatigue.

Not shame that you are not trying.

Shame that you are trying and it is not adding up.

So you do what people do when something does not add up.

You stop looking at the whole equation. You learn to survive inside the day.

That is how the silo maintains itself. It does not have to convince you that you belong there. It only has to make leaving feel like too much.

Meanwhile, the top level becomes more itself.

Places near water and mountains get more expensive because people with mobility and money choose them deliberately. Nature becomes a scarce resource. Housing starts selecting its own neighbors. Schools reflect the same pressure. Social life follows. The place becomes an identity marker, even if nobody says it out loud.

You can live in the top and still struggle. But you struggle in a place assumed to be worth investing in.

You can live in the bottom and still be noble, skilled, and loved. But you live in a place often treated like a cost center, a place to extract labor, a place where reinvestment comes late, if it comes at all.

The silo does not require cruelty to exist.

It only requires friction.

Friction is a rent you pay every day. The rent is small enough that you keep paying it, and over time it becomes your life.

The story people tell themselves is always reasonable.

I will leave when I have more money.

I will leave when I have more confidence.

I will leave when my friend leaves too.

I will leave when this season ends.

But seasons become years in a place where the days are full, the exits are expensive, and the world keeps asking you to spend your best energy on staying afloat.

The most dystopian part of the silo is not the concrete.

It is the way a place can rewrite what you think is possible, and do it so slowly you do not notice it happening.

From the outside, it looks like a country sorting itself.

From the inside, it looks like a life adapting, one sensible decision at a time, until adaptation becomes identity.

And if you ever wonder why nature keeps showing up in the top level, it is because humans are not only economic actors. We are bodies. We are attention. We are stress. We are sleep.

We move toward landscapes that make our inner life cheaper to carry.

That pull is real.

So is gravity.

And between those two forces, the silo keeps rising.